Westside

Ybarra's Market

914 Spruce St. W, San Bernardino

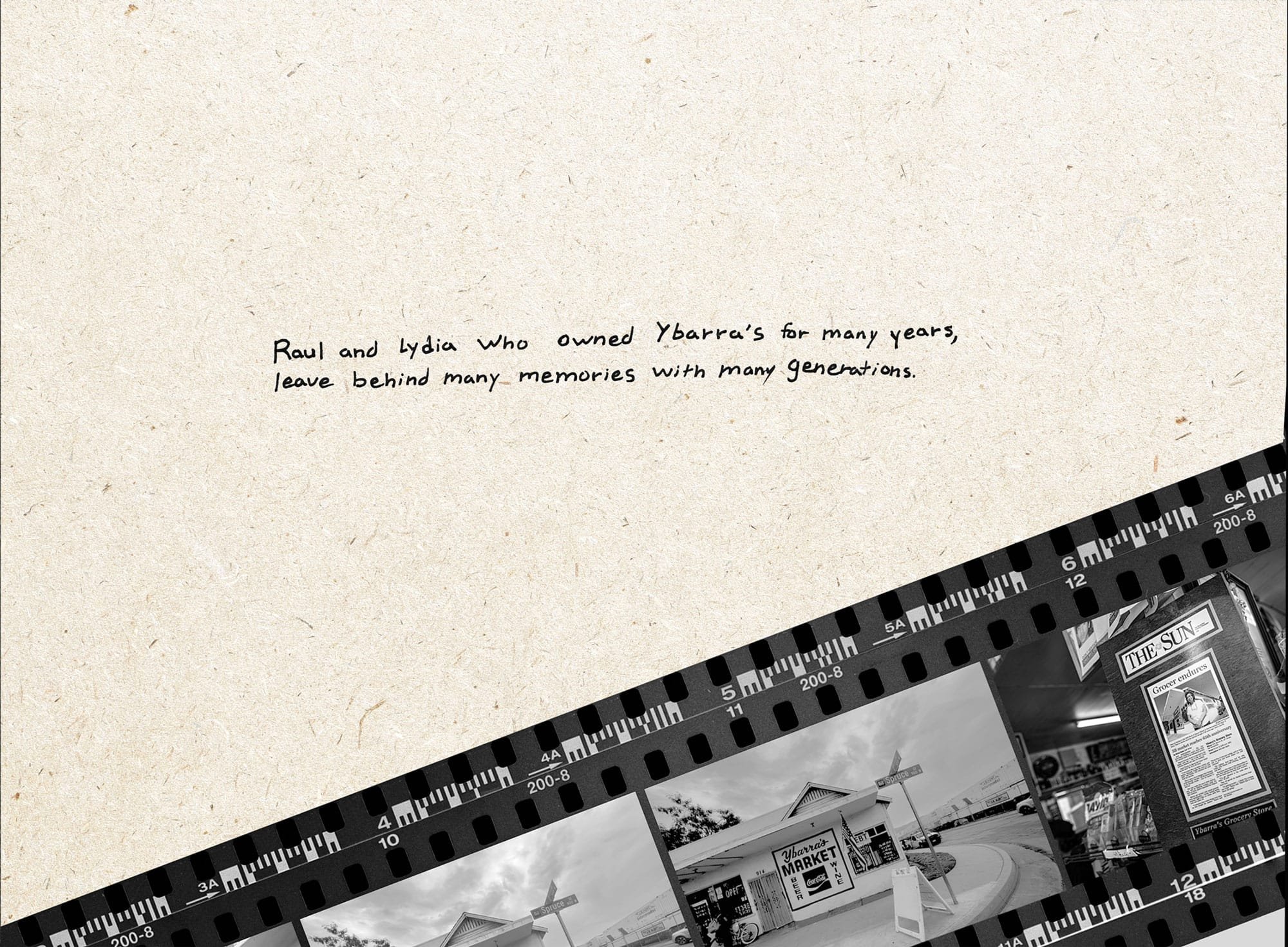

Ybarra’s Market, a historic Latino family business, has served the Westside since 1946. It has been a cultural mainstay of the community even as railcars rumbled by and the freeway sliced through the neighborhood.

Ybarra’s market has witnessed the growth of railroads and freeways and the impact of transportation infrastructure on the Westside community. Housing segregation historically confined Black and Mexican residents to San Bernardino's Westside where Route 66 ran down Mount Vernon corridor and supported a variety of Mexican and Black family businesses. The city’s decision to build a freeway (with all exits leading away from the Westside) diverted traffic off of Mount Vernon. Opened in 1959, the freeway starved neighborhood businesses of commercial traffic undermining Black and Mexican family businesses and the social fabric of the community. Called the Berlin Wall by Westside residents, the multistory freeway has continued to act as a physical barrier across San Bernardino, hardening lines of segregation. But in the midst of such rapid change and community disinvestment, Ybarra’s Market continued to serve the community with fresh groceries, Sunday menudo, and a site for gatherings after work at Santa Fe. Generations support these historic businesses and view the Westside as a source of pride, despite living in one of California’s diesel death zones.

From the Archives

by A People’s History of the I.E.

Click on the images below to uncover the story.

San Bernardino by the early 20th century was a central transportation hub in the American West, largely thanks to the Santa Fe Railway. The railyard was the economic backbone of the Westside, where generations of Mexican, African American and white workers labored in the machine shops and freight terminal.

Black and Mexican families began settling on the Westside in growing numbers starting in the early 20th century. By the 1920s, real estate agents, white homeowners, and city government began to erect formal and informal barriers to segregate Black and Mexican families on the Westside of the railroad tracks.

“It was quiet. A lot of Black, Mexican families lived here. A bit further down, Italian families. And in these homes, white families.”

—Jennie Ybarra, former owner of Ybarra’s Market.

By 1940, the Westside was a vibrant multiracial neighborhood, where Mexicans made up 50-80% of the population. The Black population was also growing (17%) between 6th and 9th Street, centered around the city's two oldest Black churches on 6th Street.

Aerial view of Santa Fe railyard between 1923–1934, courtesy San Bernardino Historical Society & Railroad Museum

A vibrant Westside business district grew from the 1920s-1950s along Mt. Vernon Ave. with small grocery stores throughout the community. In 1953, before the freeway the Westside accounted for 62% of the purchasing power in San Bernardino. “In fact, by 1959,” historian Mark Ocegueda explains, “the corner of Mt. Vernon and 5th St. served as the busiest intersection in the county with 34,000 vehicles regularly entering the junction daily.”

“In this area, there were 12 little stores… Everybody was doing their little business around the area. Like I said, that was before...the freeway came in.”

—Raul Raya, grew up above Ybarra Market, and owned it for the last 7 years.

Traffic jam, Mt. Vernon Ave., 1950s, courtesy of Mark Ocegueda & Oquendo-Montaño family collection

Andres and Pascuala Ybarra bought Ybarra’s Market in 1946. They migrated to San Bernardino from Guanajuato in April 1927. Andres picked citrus in East Highland, helped build Norton Air Force Base, and worked at Kaiser Steel. His path mirrored those of many Mexican immigrants. Pascuala took care of the family store which catered to many workers from Santa Fe.

After they retired, their daughter Jennie Ybarra ran the store for decades and then their nephew Raul Raya kept the family business going.

Andres & Pascuala Ybarra with son Carlos, 1950, courtesy Raul Raya

Jennie Ybarra remembered how her family always took care of the community by allowing them to take items on credit during hard times.

“We all went through hardship, we understand. There’s a lot of people that are grateful. And we’re [also] grateful because they were our bread and butter, you know.”

—Jennie Ybarra

These relations of trust with neighborhood stores were vital to families struggling to make ends meet when racism confined Mexican and Black workers to low wage jobs.

Virginia, Jennie, & Pascuala Ybarra and children at Ybarra’s Market, courtesy Jennie Ybarra

Train tracks ran down I Street forming a border between the Westside and downtown even in the early 20th century. Though segregation concentrated communities of color "on the other side of the tracks," the railroad tracks were a very porous boundary.

Westside residents could easily walk across the tracks to downtown. Cars likewise drove across the tracks as they followed Route 66 through the heart of the Westside.

Raul Raya, who grew up above his family’s market, would watch the trains from his window and walk across the tracks to Harding School to play with friends “on white side of town.”

Neighbors remember when the trains would sometimes stop outside Ybarra’s Market on Spruce and the train guys would get off and go to buy snacks at the market. Ybarra’s was an informal hang out for Santa Fe workers who would hang out in the back with beers on Friday nights.

Train tracks along I Street looking south from 6th St, showing street crossings, 1950s (pre-freeway), courtesy of Santa Fe Railway Historical & Modeling Society.

In the 1950s, James Guthrie — a powerful San Bernardino businessman and California Highway Commissioner — pushed for the construction of a North-South freeway through San Bernardino to address congestion on Route 66. They built it along I Street despite concerns from Westside business owners about the freeway’s potential economic impacts.

“Once the freeway came on, all the exits were running towards the east side. So that's why the Westside went down. We didn't have no access for people to come. So by the 70s, the store was starting to go down.”

—Raul Raya

Referred to as the “Berlin Wall” by locals, the 215 freeway served as a concrete barrier that divided San Bernardino and deepened segregation. The exits diverted traffic towards downtown and starved businesses along the Mt. Vernon corridor. Most streets no longer ran through, and businesses like Ybarra's found themselves isolated on streets that deadened into the freeway.

Freeway, Historic Topo Map 1959, Historical Topographic Map Collection courtesy of the USGS, Esri

The Ybarra family, like many merchants, have persevered through the economic decline of the Westside.

“We’re in a rough area,” one businessman told the San Bernardino Sun in September 1980. “But I wouldn’t move my business.”

Twenty one years after the construction of the freeway, surveys showed that the Mt. Vernon business district area became “blighted” and “in a rapid cycle of decay.”

“There’s scholars and organizers that speak about this ‘slow violence’ that is associated with the supply chain. I think this situation falls along that line of thinking. Because it took about two decades for those effects to be felt.”

—Mark Ocegueda

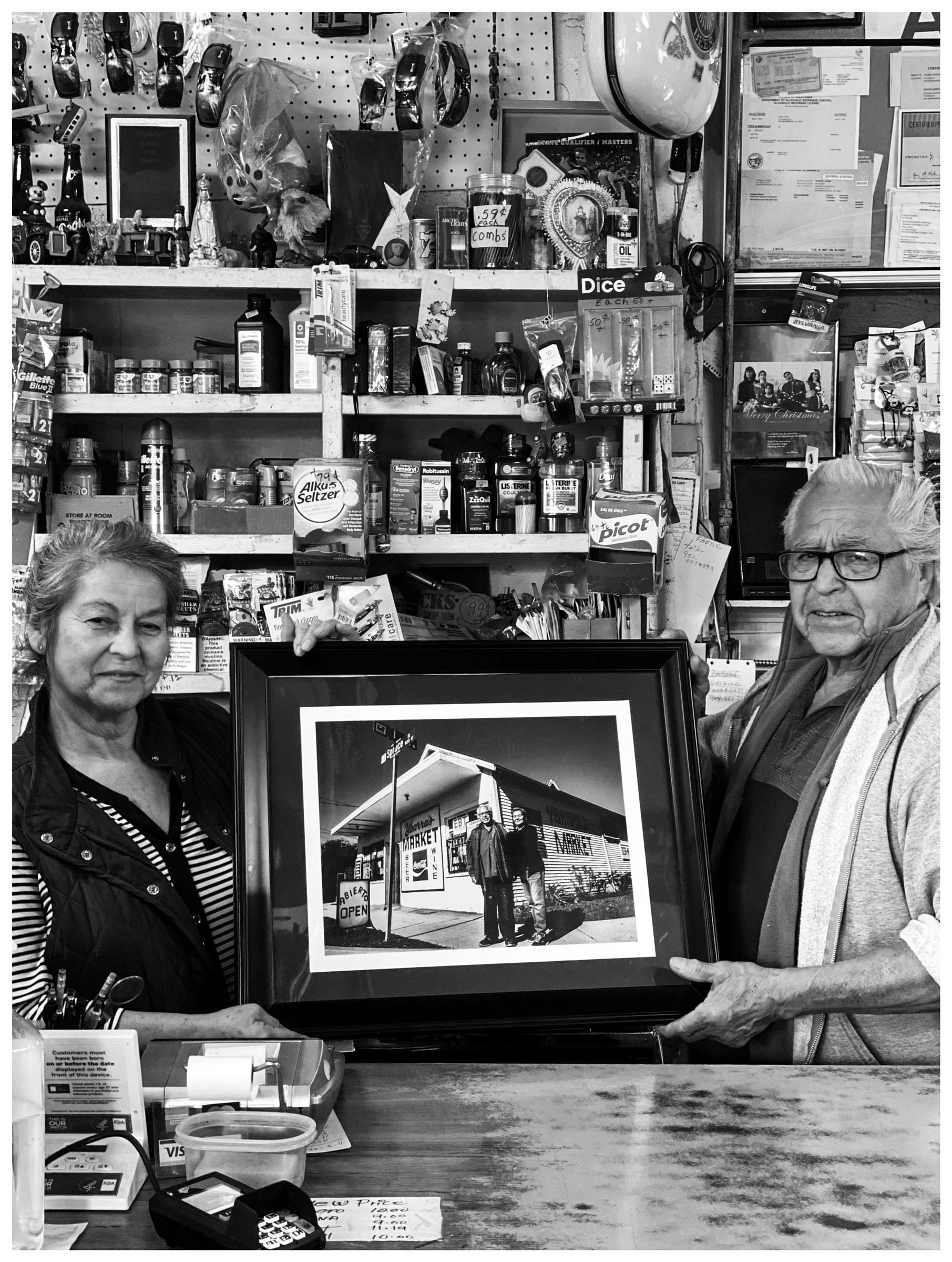

Raul & Lydia Raya in Ybarra’s Market, where he grew up and worked for many years, courtesy Rodney Muñoz

Rebecca Chacon remembers riding her bike down Spruce Street and playing along the railroad tracks with friends in the 1980s and 1990s. Her grandmother — Virginia Rooney — worked at Ybarra’s Market for over 30 years.

She saw economic stability decline in the neighborhood as major employers like Santa Fe shops, Kaiser Steel, and Norton Air Base closed by the early 90s.

“Times have changed. It will never be what it was,” Chacon laments.

Virginia Rooney with her daughter Vickie Guzman, Sylvia Rodriguez and grand daughter Rebecca Chacon, courtesy Rebecca Chacon

The freeway was reconstructed in the 2010s — this time with exit off ramps diverting traffic east AND west.

But the Westside has continued to see disproportionate impacts from the expansion of BNSF Railway and the warehousing industry. The constant parade of trucks and trains passing through this corridor have made this neighborhood a diesel death zone.

Ybarra’s Market with Amazon containers on passing train, photo by Anthony Victoria, courtesy The Frontline Observer

Residents are organizing to hold BNSF and the logistics industry accountable for improving air quality in the region by pressuring them to phase out diesel engines and reduce emissions.

Benjamin Luna says sometimes fighting massive companies like BNSF seems like an uphill battle. But, he says he finds a form of resistance in his garden next to Ybarra’s market where he grows and shares food with his neighbors, keeping the community spirit of the Westside vibrant for the next generation.

BNSF Rail Track Extension Tour Lena Kent with Alicia Aguayo right and Lucy Sunga (center), photo by Anthony Victoria, courtesy The Frontline Observer

Raul Raya put this sign up at the corner a block from the store, trying to keep the legacy of this historic business alive.

“I put it up there so that the people could see that Ybarra's was still open. We don't have that much traffic around, but the people that know us for so long, that's why we’re still open.”

—Raul Raya

In Spring 2024, Raul Raya sold the store, but new owners will keep the name and memory of this historic business alive.

Ybarra’s is Open Sign, courtesy Rebecca Chacon

It’s hard to overstate the love people have for the small Westside grocery store. When people heard of its closure, memories poured out on Facebook and Instagram.

People remembered the best menudo in town, the bologna that could be cut any thickness, and the love and care they got from owners whenever they came by. One man wrote,

“every time I walked in [Jennie] would call me m’ijo.”

A local car club organized a cruise by the shop, greeting longtime owner Jennie a block away, where she sat on the porch to be celebrated by the community.

Lowrider Car Show celebrating Ybarra family and market after the closure, courtesy of Phil Florez

At the Corner of Ybarra's

by Rodney Muñoz

Resources

-

Inland Congregations United for Change helps Inland Empire communities fight for equality, equity, and justice.

Inland Empire Black Worker Center organizes for quality jobs, economic and social mobility, and policies that ensure Black workers, their families, and the community thrives.

Inland Empire Center for Community Organizing is the hub for teaching and practicing organizing within various arenas.

Just San Bernardino represents a range of organizations involved in economic mobility, grassroots organizing, community development, and racial equity.

PC4EJ – People’s Collective for Environmental Justice fights for environmental justice and challenges the cultural and systemic roots of white supremacy.

-

Garcia Center for the Arts is a home for creatives and arts organizations as well as a community hub, with a garden, performance stage, glassblowing studio, and more.

The Little Gallery displays contemporary art from San Bernardino County and beyond.

-

Akoma Unity Center, “Youth Seek Environmental Justice.”

Frontline Observer, “California’s zero emission train and truck rules decades in the making.”

Frontline Observer, “Community Voices Concerned about New Indirect Source Rule.”

Sol Y Sombra: San Bernardino's Mexican Community, 1880-1960 dissertation by Mark Ocegueda.

-

Bridges That Carried Us Over is a community-based collaborative initiative to document Black history in the Inland Empire with oral histories, photos, and public programs.

Inland Barrios is a visual love letter to Mexican, Mexican American, and Chicanx/Latinx history in the Inland Empire curated by Dr. Mark Ocegueda.

San Bernardino History and Railroad Museum is located in the restored 1918 Santa Fe Depot, specializes in all things railroad, and houses the Santa Fe Western Archive.

A People’s History of the I.E. digital archive includes materials from former owner of Ybarras Raul Raya.

![Jennie Ybarra remembered how her family always took care of the community by allowing them to take items on credit during hard times.

“We all went through hardship, we understand. There’s a lot of people that are grateful. And we’re [also] grat](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/660db30af17a6f2004fa1946/4e3659ea-d8ba-493d-a6ae-a781c6151688/Virginia%2C-Jennie-and-Pascuala-Ybarra-.jpg)