Valley Truck Farms

St. Mark’s Missionary Baptist Church

259 E Central Ave, San Bernardino

St. Mark’s Missionary Baptist Church was at the center of Valley Truck Farms, a rural refuge for Black families from the 1930s to the 1970s that was destroyed by city zoning decisions and the expansion of a warehouse economy.

Black families bought small plots of land in Valley Truck Farms where they could build homes and grow big gardens that made many southern migrants feel right at home. These farms also insulated their families from economic insecurity over the decades as racism continued to confine Black workers to low paying and unstable jobs. They founded vibrant churches, built a Black-led school, and forged a community that sustained generations of families who fled the Jim Crow south and the confined segregated neighborhoods of Los Angeles. The Valley Truck Farm has a layered history of environmental justice struggles, shaped by city planning decisions & the neighborhood’s proximity to Norton Air Force Base. When San Bernardino slowly annexed the community after the 1960s, city officials couldn’t see the value of the homes, businesses and small farms across the rural landscape and searched for more “profitable” uses of the land. Now only St. Mark’s Missionary Baptist Church and a few scattered houses remain, surrounded by warehouses. Photos and many shared memories help us remember the story of this vibrant rural Black community. The erasure of this rural residential community serves a warning to other communities in the IE where warehouses encroach on residential developments.

From the Archives

by A People’s History of the I.E.

Click on the images below to uncover the story.

George & Eula Saville were one of the earliest Black families to move to the Valley Truck Farms in 1927. They came to the Valley because their father “loved farming.” They raised their 7 children on their 5-acre plot and stayed in the community until they died in 1988.

Looking back at the changes in the Valley since her childhood, Barbara Saville Bland asked.

“You wonder how they could destroy a community like that. Wouldn't the community have to give consent? Or could the city just take over? You know, because it's terrible. People had to move.”

George Saville at the newly built family home of neighbor Vera White, 1934, courtesy of Vera White Saville

St Mark’s Missionary Baptist Church was founded in 1929, one of the historic churches that has served as the center of community life for generations. St. Mark’s has had only 4 pastors in its 95 years. Pastor Percy Harper embodies this continuity. He grew up in the church just blocks from his home, and has led the congregation since 1986.

The church building has served many functions in addition to worship for the congregation. It temporarily housed families displaced by the great flood of 1938 and served as an overflow classroom and auditorium for Mill School through the 1940s, 50s and 60s. The county even ran well-baby clinics at the church.

The World Wide Guild, a women’s missionary group, in front of the first St. Mark’s Baptist church building 1940s, courtesy Pastor Percy Harper

“We had cows, chickens, rabbits. We had a giant garden… Everything. Most of the things that we ate, we raised, and we all grew up healthy that way….I never went to the doctor because we ate fresh non-pesticide food. And all my brothers and sisters, we all stayed healthy until we left home.”

—Rennie Green

Edmund Greene remembers milking his neighbor’s cows for a share of the milk, and getting okra from neighbors that you couldn’t buy at the store. “If we had extra stuff, we’d drop it by people's houses that we knew needed it.”

In 1972, in an effort to combat poverty, neighbors developed the Valley Truck Farms Community Center Corporation to formalize this sharing economy. In the summer of 1975 they received a grant to employ 200 young people who learned gardening from community elders and shared the produce with needy families. The San Bernardino Sun celebrated how “young and old joined hands to build a garden oasis.”

Garfield Hinchen with his grandchildren visiting the animals on the farm, courtesy Janice Wilson

Excel-All Women’s group was founded by Espanola Larkin and other women in the Valley community in the 1950s. As reported in the Valley Truck Farms Scrapbook, "Their Lincoln Avenue Clubhouse hosted children's plays, music functions, and Saturday night entertainment." They also helped mobilize the community to vote and support the schools. From 1947 to 1960, Mrs. Larkin also wrote, typed, and distributed a monthly one to three page newspaper called The Valley Scroll.

Excel-All Women’s group with Eula Saville, Mrs. Larkin, Alice Sneed, Mrs. Jackson, and other as yet unidentified community members, courtesy Donald Jackson

Valley Truck Farms was home to many entrepreneurs. Some started small businesses like candy stores or hair salons out of their homes and neighborhood store fronts. Ola McDowell and her husband ran McDowell’s Cafe on the corner of Waterman Ave. and Norman Road in the 1940s and 50s. Later the Overstreets would run Spotlight Cafe and several other businesses at Waterman & Central.

“The buildings are all gone. We had the cafe. We had a store. We had a pool hall. We had a printing shop and we had a barber shop... And the city had us tear those buildings down.”

—Annette Overstreet

Annette Overstreet cutting hair in the small salon that she ran from her own home, courtesy Annette Overstreet

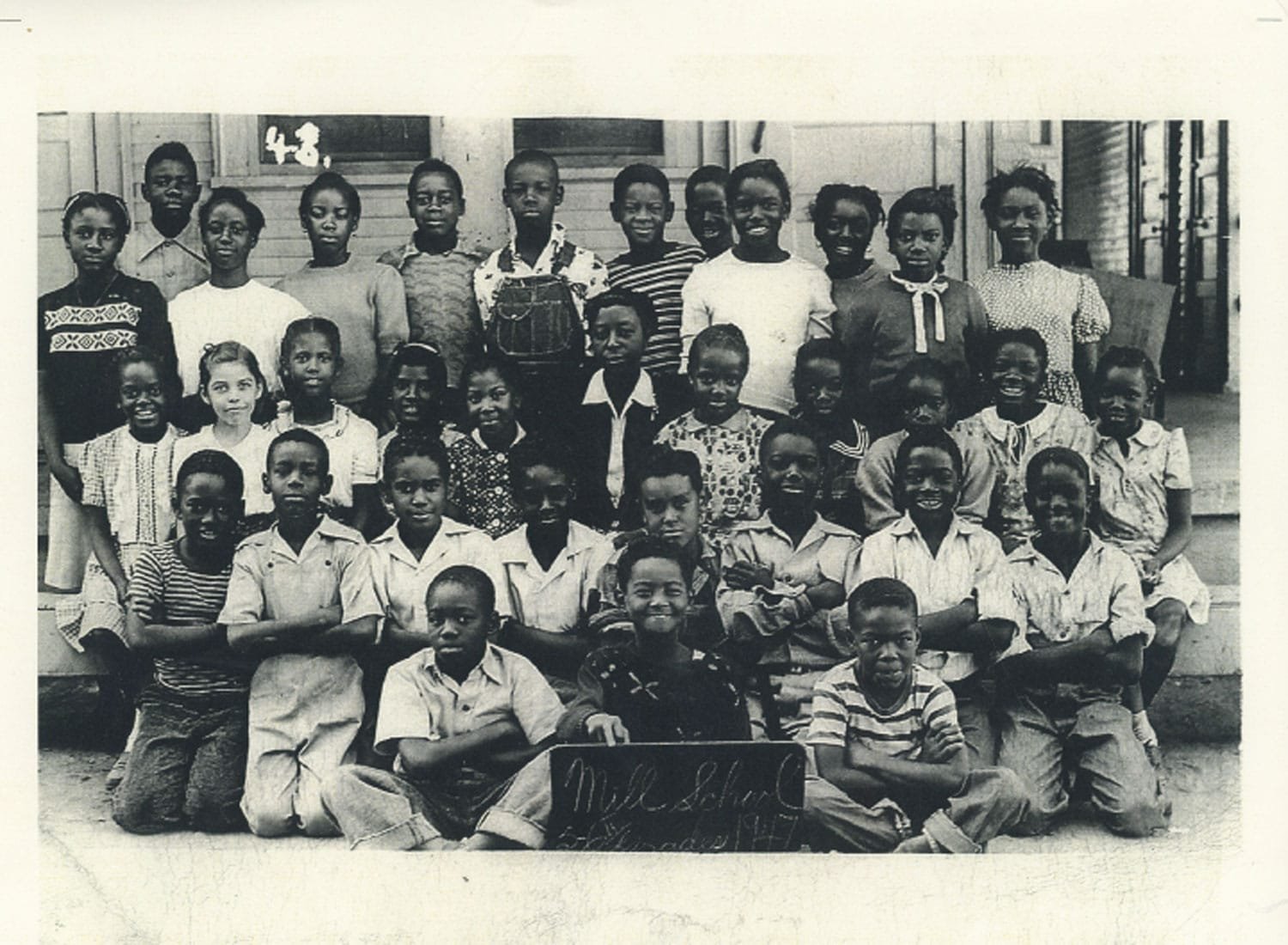

By the 1940s, Dorothy Inghram became a teacher and then principal at Mill School. She demanded excellence, recruited Black teachers, and helped pave the paths to higher education for many students. Ms. Inghram resisted the implicit limitations placed on too many Black children.

“We were being taught how to clean houses. Now, that was what ticked her off big time. So eventually she got everybody together, and it was kind of like, 'You are going to learn. You will read. You will not tell me No." You know, and so it was just kind of a big deal.”

—Irma Jackson Forward

After the second Black teacher was hired, most white students fled the school until the San Bernardino School District began to refuse the transfers. Mill School was closed in 1968 as noise pollution escalated from Norton Air Force Base and officials worried that the flight path put the school at risk.

“The day I saw that they tore the school down, it actually brought tears to my eyes because that was the last vestige of my childhood.”

—Dennis Green

Second grade Mill School class photo from 1947, courtesy Annette Overstreet

The community really invested in young people. Greta Mixon visited with neighbors Mr. and Mrs. Merrill Harper, who had a pig farm across from their home.

“I remember even in college, when I would come home on break, I would come over. Hey, mom, how are you doing? Drop my stuff off. I'd go across the street and sit out in that front little porch area. They would tell me everything that was going on in the Valley.”

—Greta Greene Mixon

“I think all of us were affected in a good way, by the community that we had, growing up with some of the older people, and the wisdom that they had. I remember when I was leaving for college….Some of the older people you know how they give you gifts… I got handkerchiefs from them. I got money from them. But always what you got from them, this is gonna make me cry now, um, was a send off that said, “We didn't get a chance to go to college, but you do. Remember that and do well.” And that was their send off…”

—Denise Brue-Clopton

Community gathering in Valley yard to share the catch from a fishing trip, courtesy Janice Wilson

The Valley was a checkerboard of city and county land. Neither invested in infrastructure for the rural neighborhood. Roads remained mostly dirt without sidewalks or street lighting and the community had to advocate for recreation facilities.

Some, less desirable, investments in the neighborhood came more readily. In the 1970s, residents complained about the stench from the city’s nearby sewage treatment plant that was located in the Valley. In the early 1990s a hazardous waste transfer station was built on a residential street in the community.

Girl on Valley Truck Farms property, Greene Family Photo Album, courtesy Edmund Greene

Cold War military industries, with Norton Air Base and Kaiser Steel, expanded job opportunities for many Valley residents. Norton also degraded the environment of the Valley and threatened homes and schools.

New EPA regulations passed in 1969 banned federal housing assistance in areas with high noise, which impacted many communities in the Norton flightpath. Cities like Redlands got the flight paths shifted to protect FHA loans and future residential development. Close to the Air Base, the Valley didn’t have similar political advocates protecting the residential community.

"During the Vietnam War when the jets were loaded, they would take off three at a time, and they would fly so low in the neighborhood that you could actually see the pilot's helmets in the cockpit. Certain streets couldn't have the TV antennas mounted on the roof of the house. They put them on the side of the house because the planes came that low and they were loaded, going to Vietnam.”

—Rennie Green

C-114 Starliner, 1980, courtesy of National Archives

As early as 1952, Irma Jackson Forward remembered that her mom’s boss, the president of a downtown bank, told her that the city had plans for Valley Truck Farms. When she mentioned plans to maybe move, he warned, “Wait before you sell so that you can get the most for your money…cause all of this is going to be industrial.”

By the mid 1970s, homeowners struggled to access federal funds for residential rehabilitation because of the proximity to the airport. As more of the Valley became incorporated into the city, Dennis Green remembers,

“Everybody’s property taxes start going up because of the new commercial zoning on your shack. Because they won't let you remodel it. They won't let you repair it. But now you've got a commercial lot.”

Rennie Green remembered how his neighbor worked around the new rules. “She brought a house… in on a truck and dropped it on her property. And the city couldn't do anything about it.”

Sally Morris & Maxine Baker Ramsey in front of St. Mark’s Missionary Baptist Church, 1970s, courtesy Annette Overstreet

By the mid 1970s, some neighbors already recognized the writing on the wall that the “area had no future as a residential area.” They organized the South Waterman Homeowner’s Association to help residents navigate the change.

At a 1974 meeting with city leaders, Pastor George Scott added, “This is one of the areas left where a profit can be made. These men will see to it that a profit will be made. The question is will you share in it.”

“It was planned over a period of time. They take over the area from the county, convert to the city, change the zoning, condemn your property to where you could not make any improvements or rebuild it if it caught on fire. So they could describe it as a blighted area, low value…So you sell your house, they bulldoze it, level the land, and now it's prime commercial property. The first person that turns it over makes no money. The second person that turns it over makes all the money on your livelihood.”

—Dennis Green

Edmund Greene in his family’s flower garden on Foisy & Norman Road, 1970, courtesy of Edmund Greene

“They've wiped out the history and the past of the Valley Truck Farms. It no longer exists because of all of the construction that's going around big box warehouses.”

—Dennis Green

Even though the historic Valley community is mostly gone, small neighborhoods still stand surrounded by warehouses growing up around the San Bernardino airport. The San Bernardino Airport Communities coalition is mobilizing residents around the old Norton Air Base to improve air quality and fight for better paying jobs that will lift up the surrounding community.

Church doors open out to warehouses, courtesy of Tamara Cedré

Remembering the Valley

by Tamara Cedré

Annette Overstreet & Myrna Overstreet Spear, 2024

Overstreet Album, 2024

Truck Yards off Norman, 2024

Norman Avenue, 2024

Pastor Percy Harper, 2024

Hymnal, 2024

St. Mark's Missionary Baptist Church, 2024

St. Mark's Lobby, 2024

Sunday Service, 2024

Church Doors Opening Out to Warehouses, 2024

Pulpit, 2024

Cross, 2024

Robes, 2024

Benediction, 2024

Children's Art, 2024

Front Row, 2024

The Great Commission, 2024

Vera Seville, 2024

Vera's Front Yard, 2024

Vera with her Brother in the Front Yard, 1957

Vera's Backyard Facing a Truck Yard, 2024

White Family Homestead Document, 2024

South Waterman, 2024

Vera's Dad on the Farm, 2024

Church Portraits

by Jonathan Arthurs

Deacon Donald Jackson and Althea Jackson, 2024

Juliette Lynch, 2024

Annette Overstreet and Myrna Overstreet Spear, 2024

Deacon and Bobbie Owens (Faithful Covenant Missionary Baptist Church), 2024

Ja-Nair Johnson, 2024

Sharon Saunders, 2024

Margie Cooper, 2024

Pam Malone and Deborah Taylor, 2024

Mr. and Mrs. Dennis Green, 2024

Darlene Jefferson, 2024

Ricky Van and Niece Mylove, 2024

Paulene Thomas (seated) and Eugenia Lucus, 2024

Carolyn Tillman, 2024

Annette Brewer and Pamela Pete, 2024

Mariam Williams, 2024

John Coleman, 2024

Janice Wilson (seated right), Danisha Childs (standing right), and family, 2024

Pepper Harper, 2024

Tamika and Darlo Murray with Malaiyah, Noelle, and Darshawna, 2024

Pauline Aciero, 2024

Deborah Harper, 2024

Caroline Harper, 2024

Rhonda Fair Cunningham, 2024

Melba Redd, 2024

Remembering the Valley

A Short Film by Tamara Cedré

Celebrating the Valley

by Tamara Cedré, Jonathan Arthurs, and A People’s History of the I.E.

Installation of church portraits by Jonathan Arthurs with Historic Landmark sign, St. Mark’s Missionary Baptist Church, July 28, 2024. Photo: Tamara Cedré.

96th Anniversary Celebration of St. Mark’s, Nov. 17, 2024. Photo: Catherine Gudis.

Photographer Jonathan Arthurs working on photo installation, July 26, 2024. Photo: Tamara Cedré.

Visitors Star and Aicheria Bell (left and right) with Jeanice Inghram who grew up in the Valley, July 28, 2024. Photo: Catherine Gudis.

Installation of archival and new photographs of the church and congregation by Tamara Cedré, 2024. Photo: Audrey Maier.

Screening in the church sanctuary of Valley Truck Farms video by Tamara Cedré, 2024. Photo: Catherine Gudis.

Member of the congregation with a photo of herself as a child living in Valley Truck Farms, July 28, 2024. Photo: Catherine Gudis.

Families from Valley Truck Farms reminisce over historic photos, July 28, 2024. Photo: Audrey Maier.

Celebration of Valley Trucks Farms at St. Mark’s, with Deacon Donald Jackson at left and, in the background (left), the home he grew up in, now one of the few remaining original Valley houses, 2024. Photo: Jonathan Arthurs.

Deborah Harper, Deacon Jackson, and Althea Jackson at celebration of Valley Trucks Farms at St. Mark’s, July 28, 2024. Photo: Jonathan Arthurs.

Adrian Metoyer III, Chef Spank, Pastor Percy Harper, and Trap Kitchen at St. Mark’s celebration, July 28, 2024. Photo: Jonathan Arthurs.

Pastor Harper, who has served St. Mark’s since 1987, at the 96th church anniversary celebration, Nov. 17, 2024. Photo: Catherine Gudis.

Resources

-

Inland Empire Amazon Workers United builds worker power to fight and win safe jobs, a living wage, and the freedom to organize without retaliation.

San Bernardino Airport Communities is a coalition of community members, labor unions, environmental justice groups, and faith-based organizations fighting for the vitality of communities living near the San Bernardino Airport.

-

A People’s History of the I.E., Valley Truck Farm StoryMap visualizes the narratives that are part of the Valley Truck Farm Scrapbook.

A Valley Truck Farms Photo Gallery: Family photos and stories display the archives documenting Valley Truck Farms in a People’s History

Frontline Observer, “Airport plan aims to build on San Bernardino’s logistics growth.”

Frontline Observer, “Facing evictions, residents join community groups in denouncing San Bernardino Airport’s development plans.”

KVCR, “Airport Gateway Specific Plan “no longer moving forward.”

Valley Truck Farm Scrapbook commemorates the history and community of this southeastern rural neighborhood of San Bernardino County.

-

A People’s History of the I.E. is a community-based digital archive that includes a growing collection of photographs and oral histories documenting the people and places of Valley Truck Farm.

Bridges That Carried Us Over is a community-based collaborative initiative to document Black history in the Inland Empire with oral histories, photos, and public programs.