Fontana

Kaiser Steel

13340 San Bernardino Ave. (@ California Steel Wy.), Fontana

Henry Kaiser’s 1942 Fontana steel mill, the first of its kind on the West Coast, flourished during WWII and through the Cold War. The plant supplied materials to feed the postwar consumer spending spree, all while laying the groundwork for the region's new empire of logistics.

Kaiser made a name for himself constructing roads, dams, and cargo ships — key infrastructure for California’s growth. He challenged eastern Big Steel by taking federal wartime loans and vertically integrating his production from raw materials to finished plates, girders, pipes, and millions of heavy artillery shells. With furnaces blasting and open hearth pits flaring, business boomed at Kaiser. Its bust came with 1970s-era global competition. At its peak Kaiser employed 9,000. These jobs were lost. The Superfund-rated toxic nightmare remained. Decades later, a racetrack and millions square feet of distribution centers fill the Kaiser property, with a master plan to develop another mega-logistics site. Tract housing developments sit next door to miles of salvage yards, recycling plants, and trucking companies, all memorializing Fontana’s military and industrial past.

From the Archives

by A People’s History of the I.E.

Click on the images below to uncover the story.

“From Pigs to Pig Iron!”

—Kaiser Steel Mill slogan, 1943

Fontana in the 20th century was an early agribusiness promoted through romanticized imagery. By the 1910s and 20s the town was planted with 95,000 citrus trees and acreage devoted to chickens, rabbits, and the world’s biggest hog farm. Its pastoral appearance could be deceiving.

“Old-timers remember the competing stenches from the excrement and the garbage,” according to Ernie Garcia. L.A. shipped its trash here to feed the pigs, whose manure then fertilized the groves.

Fontana’s seasonal employment at harvest time included immigrant workers from many nations. Sherman Institute, the off-reservation Native American boarding school in Riverside, also sent hundreds of Indigenous youth to work at Fontana’s farms.

Photo: Hog ranch, Fontana, c. 1935, courtesy Los Angeles Public Library, Earl Powell Chamber of Commerce Photo Collection

“Fontana Steel Will Build a New World!”

Fontana Herald-News, January 7, 1940

Fontana’s 2.5-acre lots were large enough for a garden and hen house. They promised settlers self-sufficiency and a reprieve from the smokestacks of urban industrial life back East. Until 1942 at least.

Kaiser tried to set his mill apart from other steel towns. He promoted the aesthetics and landscaping, suggesting the mill was in harmony with citrus groves. Citrus grower Minnie Luksich was among those who weren’t convinced. She had opposed locating the plant in Fontana, fearing the emissions. She later said “We didn’t have money to do one thing about it.” Eventually she got a job there.

Photo: Blast Furnace, Kaiser Steel, 1944, American Iron and Steel Institute, courtesy Hagley Library and Museum

In 1950, more than 5000 acres of orchard and vineyard land surrounding the Kaiser plant was put on sale by an L.A. realtor, for “private, defense industry development.” Cold War military expansion at nearby air bases continued the market for steel. The smoke in the press photo draws attention, though, to environmental issues Kaiser faced from the start. The height of the smokestacks aimed to lift the fumes up and away. It didn’t work.

Some locals saw the towering smokestacks as polluting the valley and destroying its crops and way of life. Others put it bluntly, as one ex-steelworker later said: "Hell, that smoke was our prosperity.”

Aerial view of Fontana with Kaiser Steel at center, 1951, © U.S. Chamber of Commerce, courtesy of Hagley Museum and Library

From 1948, Kaiser mill was fed by iron ore mined from Eagle Mountain, adjacent to today’s Joshua Tree National Park in the Mohave Desert. Kaiser created an entire company town to work there, tapping water from the Park to keep residents’ lawns green and the community pool open. His crews laid 52 miles of tracks for his private railcars to carry ore from the mine to the Southern Pacific line at Ferrum (near the Salton Sea) to Fontana. It also served as a tourist destination.

The ranch houses and bungalows at Eagle Mountain still stand, as a ghost town. Park advocates resisted plans for the land to be used as a waste dump. The current owners have not revealed their intent for the property.

Here’s the part of the excursion on the Eagle Mt. railroad of Kaiser from Ferrum up to the mine, 1950. © Richard Steinheimer, courtesy of DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

Both iron mining and steelmaking are water and energy intensive, using fossil fuels to create hot enough temperatures to smelt iron and coal into steel.

Kaiser Steel never contributed to the city’s tax base. It remained unincorporated with its own water and power systems. Its toxic emissions and wastewater did not stay so confined. Rather, the mill released huge quantities of arsenic, chromium, lead, and other hazardous air pollutants into nearby communities.

“Think Safety” reads the sign on the wall next to the enormous furnace, across the bridge from the Lilliputian at right, c. 1958. Will Connell Collection, courtesy California Museum of Photography, University of California, Riverside

Fontana became home to an uneasy mix of people as thousands poured in and struggled to find housing. They lived in temporary dormitories, trailers on and off Kaiser grounds, and their cars. Racial restrictions confined Black families north of Foothill Blvd. Latinos were concentrated south of I-10. Blue-collar whites were in the center of town. From 1943 through 1964, braceros from Mexico filled agricultural jobs opened by people sent to war and into better union positions.

The stark color line and history of Klan activity in the area led to violence in December 1945 when O’Day Short moved with his family to Fontana to start a new job at Kaiser Steel, settling in a white neighborhood. They were visited by vigilantes, likely Klansmen, and the Fontana Chamber of Commerce offered to buy them out. A few nights later, a fire consumed the house, killing the family of four. Though witnesses claimed it was arson, and an NAACP investigator also deemed it so, the grand jury refused to allow witnesses on the stand and the DA labeled the fire an accident.

Vigilante Terror in Fontana, 1946, courtesy Bancroft Library

“Now, back in the day, they generally gave our kind of people dirty, nasty jobs. And so you had to endure those. But the one thing about it, unions, security and union seniority kind of prevailed.”

—Dennis Green

In the 1940s and 50s as industrial jobs grew, Black workers found new opportunities, but remained confined to the most hazardous, hot, and toxic work. Many men from San Bernardino worked for Kaiser Steel, as did 3 generations of the Green family, starting with Ernest Green. He brought his Pittsburgh steel mill experience to their new life in California. Until legal mandates were in place in the 1960s, job placement for Blacks remained restricted to the worst jobs.

Herbert Green when he retired from Kaiser Steel in 1978 after 45 years in the industry, courtesy Dennis Green

“Kaiser Steel needs a motor tune-up in its hiring policies…Unemployment is high and few Negroes are being hired…The few hired are put on as laborers despite whatever skills they might have, and are sent to the least desirable and dirtiest jobs — in the foundry, blast furnace or coke oven.”

—California Eagle, 1959

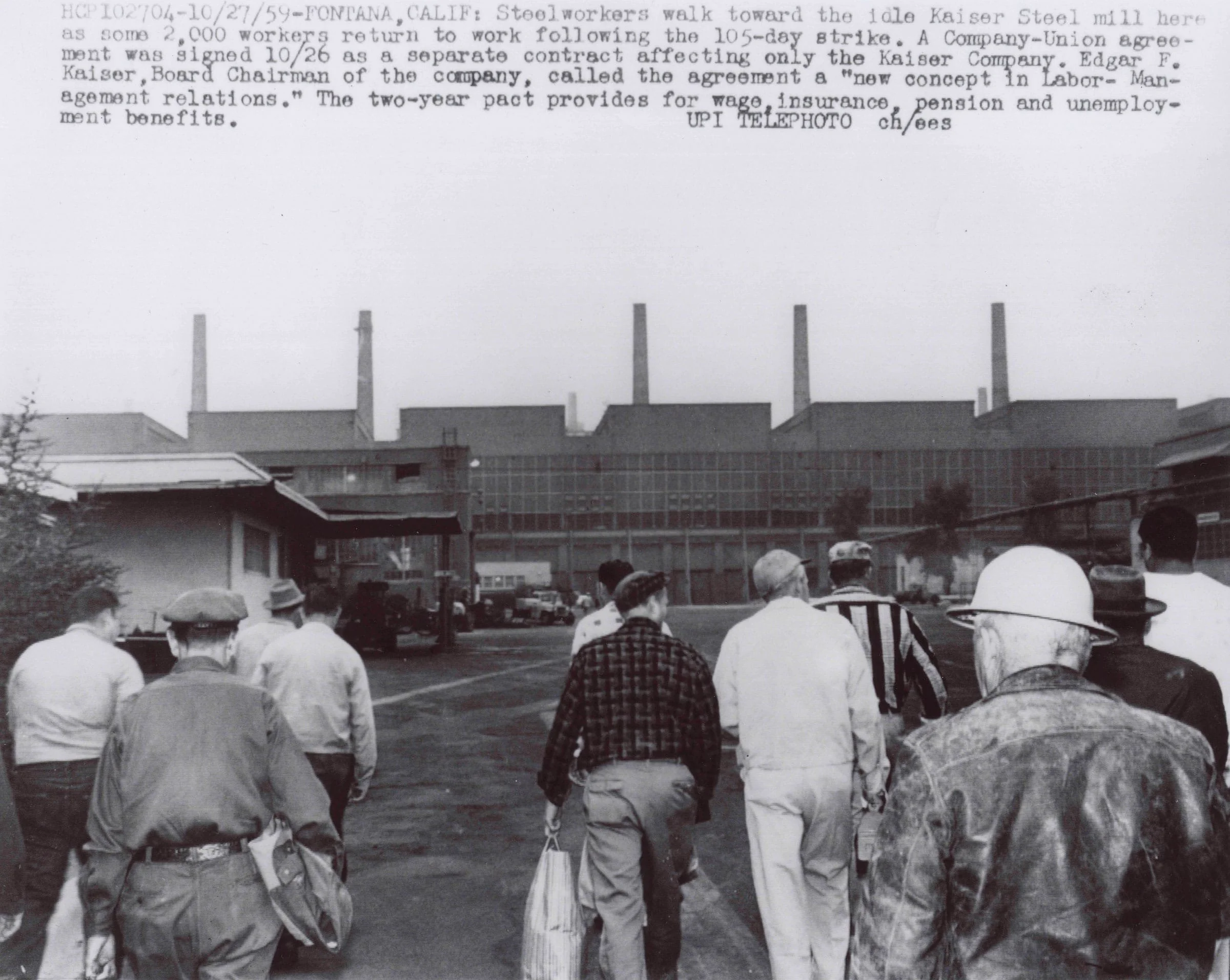

Kaiser saw himself as a benevolent industrialist, recognizing that healthcare and bonuses were a way to keep workers loyal. But frequent layoffs also meant these jobs didn’t always lead to economic stability. The 105-day industry-wide steelworkers strike of 1959 had such issues at its core.

Some, like Raymond Robinson, Kaiser’s Director of Public Affairs, when interviewed in 1976 felt this was the beginning of the end.

“As a result of that strike, the Japanese got a strong foothold in our steel market. Prior to that time, only two percent or so of the steel consumed in the seven western states…came from overseas. During that long period when our customers couldn't buy steel, they began to buy it from the Japanese. That's where it got started.”

Fontana steelworkers return to work, UPI photograph, Oct. 27, 1959, private collection

Kaiser Steel declared bankruptcy in 1983, sold its machinery to a Chinese company, and slowly sold its property holdings. Aerial maps of Fontana today reveal how industrial and warehouse uses have replaced steel manufacture, with a corresponding loss of union jobs with benefits.

Freeways and railways that facilitated distribution for the steel industry now speed up the movement of all kinds of goods to and from warehouses. Distribution centers cluster along and at the intersections of the 10, 15, and 60 freeways.

South of the 10 is especially dense with warehouses, truck yards and truck stops. South Fontana Concerned Citizens Coalition is among the community groups that have opposed warehouses being built next to schools, trucks rumbling through their neighborhoods, and the poor road and air quality. After California’s Attorney General filed a lawsuit against the City, a community benefit fund was set up to “mitigate environmental impact.” It does not stop new construction.

Aerial view of warehouses clustered at junction of I-10 & I-15, including the NASCAR racetrack that took over a portion of the former Kaiser Steel property, courtesy ESRI Aerial Basemap.

Trucks and warehouses have altered the state of work and the landscape of Fontana. Maninder Singh is a truck driver from Punjab who lives in the neighborhood. He’s among those in his family that began arriving in Fontana in the late 1980s, joining the tens of thousands who, with Mexican and Central American drivers, constitute about half of all truckers in California. Singh explains,

“In the beginning when the Amazon warehouses first came in [to Fontana], they had no restrictions on where the trucks could go. You couldn’t even get out of your driveway. And right when you left the community, there’s a friggin' line of trucks just to go anywhere.”

Singh chalks it up to a lack of municipal accountability, claiming that the city approves zoning changes, takes property, and turns around to sell it to warehouse developers. “These big companies," he says, “are just buying up all the land in Fontana.”

One of numerous truck yards in Fontana, 2024, photo by Tamara Cedré, courtesy of the artist

Steel Dreams | Fontana

by Tamara Cedré

Electrostatic Precipitators at Kaiser Steel, American Heritage Publishing Archive, 1959

Reproduction from negative, gelatin silver print photographs

Private collection

Steelworkers Strike at Kaiser Steel Plant, Associated Press, 1959

Reproduction, archival pigment print

Private collection

Xerox of Richard Serra’s Stacked Steels Slabs (Skullcracker Series), 1969, constructed at Kaiser Steel, Fontana, in Maurice Tuchman, A Report on the Art & Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967-71, 1971

Reproduction on dibond

Private collection

Structural Steel Erection at Kaiser Steel, Frashers Fotos, 1952

Reproduction, archival pigment print

Private collection

Tamara Cedré

Kaiser Steel Mill Looking Northwest, 2024

Archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist

Tamara Cedré

Kaiser Steel General Catalog, 2024

Archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist

Pat Le Roy (Secretary, 19 years old), sitting on grass in front of Administration building at Kaiser Steel Mill in Fontana, 1952

Reproduction, archival pigment print

USC Digital Library, Los Angeles Examiner Photographs Collection

Eagle Mountain Mine—Housing Area, Mine and Beneficiation Plant in Background, c. 1948

Gelatin silver print photograph

Fontana Historical Society

Mojave Desert Ore Dravo, 1965

Advertisement

Private collection

Tamara Cedré

Eagle Mountain Company Town, 2024

Archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist

Tamara Cedré

Warehouses on Almond Avenue, Fontana, 2024

Archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist

Fontana Travelodge, 1959

Advertising brochure

Private collection

Tamara Cedré

Fontana Travel Log, 2024

Archival pigment print

Courtesy of the artist

Kaiser Steel Productions, 2024

by Tamara Cedré

Montage of vintage film footage

Courtesy of the artist

Resources

-

CCAEJ – Center for Community Action and Environmental Justiceis a community-based organization fighting for environmental justice and equity in Bloomington and throughout the I.E.

Inland Empire Labor Institute partners with economic, social, and environmental organizations to prioritize the needs of workers in communities and families.

PC4EJ – People’s Collective for Environmental Justice fights for environmental justice and challenges the cultural and systemic roots of white supremacy.

South Fontana Concerned Citizens Coalition is founded by local residents who work to ensure their community has the resources they need. @southfontana

-

City of Quartz by Mike Davis documents the history of Fontana in the chapter “Junkyard of Dreams.”

Climates of Inequality, “Kaiser Steel and the Slow Violence of the Supply Chain.”

Plug In I.E. and I.E. Labor Center, “State of Work: Transportation, Distribution and Logistics Report” (Feb. 2024) includes data and interviews with residents of the I.E., including Fontana.

-

Fontana Historical Society stewards archives related to the area, including Kaiser Steel, oversees two historic sites (one that was a foreman’s house on A. B. Miller’s ranch, which now serves as a museum), and has a history room at the Fontana Public Library’s Lewis Technology Center.

UCR ARTS California Museum of Photography holds the archives of Will Connell (over 15,000 negatives and prints), who photographed Kaiser Steel in Fontana for the company.